Maus

By Art Spiegelman

Published 1991

7 min read

Maus is difficult to pin a genre on. It’s all at once a memoir, a biography, a history, and a documentary. First off, it’s a comic book about the author’s relationship with his real father Vladek who survived the concentration camps of Nazi Germany. We see the author, Art, actively interviewing his dad about his experiences. It will then jump to Vladek’s story told through his voice.

Vladek’s story is incredible. He starts off as an attractive upper middle class Polish Jew. Vladek has a drive within himself that shows throughout the story. This drive propels him to make connections, start businesses, and become wealthy before the war. When the war starts, for a while this drive keeps him and his family relatively safe. His connections help him through the underground and black market to find supplies and escape the Gestapo as they hide in one ghetto after another. They last a long time in the ghettos. Longer than most by his story.

He says by the end they had heard enough consistent rumors they knew the camps were a death sentence. They knew they had to stay out of them by any means necessary. He and his first wife decided it was safer for the kids to stay with an aunt in a different Polish city. They thought it was outside German control. They were wrong. In a powerful scene, he finds out later that instead of letting the Nazi’s take the kids, with the Gestapo banging on the door, the aunt feeds the kids and herself lethal poison. They were probably the lucky ones.

At times, the pacing is actually too fast. There are some truly horrific events that should have more weight behind them. But the story moves so fast I didn’t have any time to contemplate them before we were onto the next horrible event. That said, now that I have my own kids, there’s a couple scenes involving children that I still think about.

When he is finally captured in the final year of the war, he is lucky in many ways. He is lucky he enters the camp young, strong, and healthy. He is lucky that the war would end in only 10 months, making his survival through the camps possible. He personally endured so many atrocities. Starvation while packed in a cattle car, walking over mounds of corpses to get to the bathroom while sick with typhoid fever, the endless Death March. He saw them throwing people alive onto burning mass graves. He talked with prisoners who worked the gas chambers. He is lucky that the same drive that propelled him in business also helped him in the camps trade and work for food and other necessities.

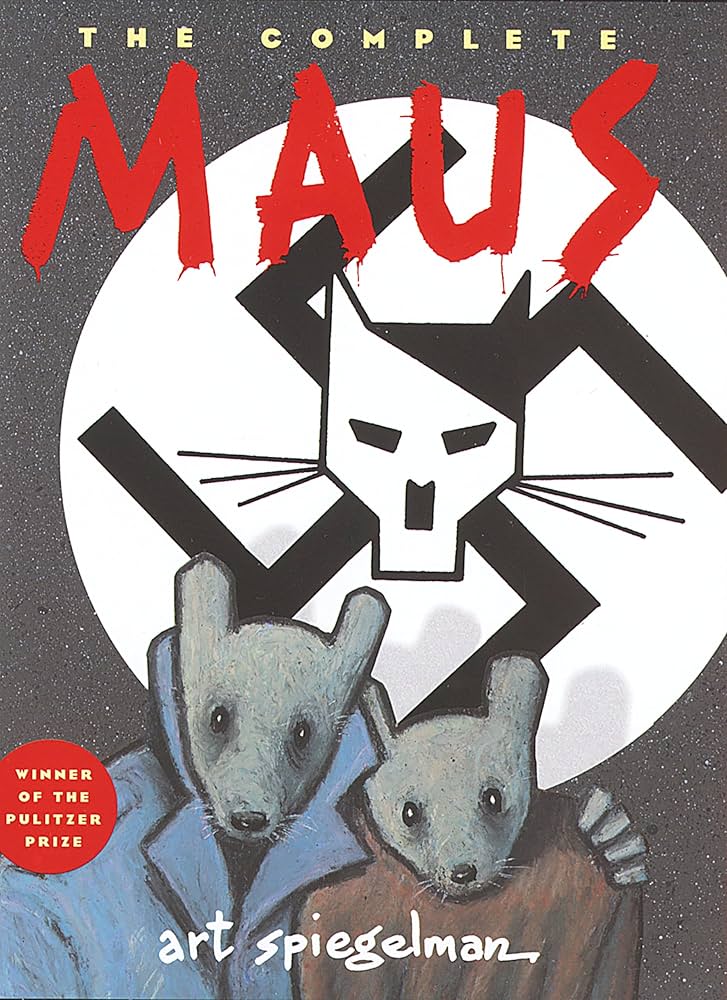

In a controversial, and dare I say, subconscious move: Art depicts all Jews as mice, all Nazi’s as cats, and all gentiles as pigs. But they don’t do mice or cat things. You could redraw them as humans and the story would not change. The only time it’s used is when Vladek has to hide in plain sight as a non Jew- he wears a pig mask.

One criticism I have is that these anthropomorphized characters have no distinguishing features. They all look so similar at times it’s hard to tell who’s speaking. Was that a conscious choice by the author? If so, it could be interpreted as everyone, regardless of station in life, are all the same. People are people. But on the other hand, by making everyone segregated into animals- it’s furthering a racist view of a people as “other.” Perhaps there’s even a bit of subconscious self-blaming going on - cats eat mice.

Spaced between chapters of Vladek’s story we also get glimpses of the generational trauma present in Vladek and his family today. Vladek could best be described as a minor hoarder, always reusing and recycling things. There’s a scene where Art and Vladek are taking a walk and Vladek picks up a piece of wire to bring home. It prompts an argument between the two. Vladek claims it can be used to tie something together, not anything needed immediately, mind you, but in the future it could. But Art knows it’s just junk lying on the ground and he could buy Vladek a whole new roll of metal wire.

His current wife is also a camp survivor yet she doesn’t have the same hoarding impulses. Her problem is money. Vladek has done well for himself after the war, but he’s very frugal. So much of his experience in the ghetto was saving every little scrap he could get his hands on. His current wife, being largely retired, is always asking him for money for things like a manicure or a replacement pair of pantyhose. We don’t get any insight into her experience in the camps, but we can assume it was likely similar. Vladek feels unsafe giving up money, she feels a lack of support from him and around and around they go in a way that shows just how much they are both still traumatized.

There’s so many avenues of dissection you can take Maus. I imagine this was assigned reading in a lot of high schools. And it should be held in the same regard as The Diary of Anne Frank and Night by Elie Wiesel. I highly recommend Maus.

- Posted on Mon, 22 Sep 2025

Review Graphic Novel Nonfiction ReadingLatest Articles

The Castle Of Otranto

10 min read

Posted Wed, 31 Dec 2025

The Haunting of Hill House

2 min read

Posted Tue, 09 Dec 2025

The Graveyard Book

3 min read

Posted Sun, 02 Nov 2025

A Storm Of Swords

3 min read

Posted Thu, 16 Oct 2025

Maus

7 min read

Posted Mon, 22 Sep 2025